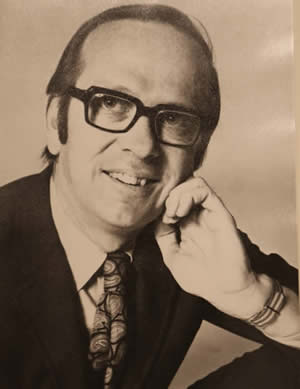

Painting by William Adie, 24 x 24, Acrylic on Linen, 2011W William Adie passed away this year. Bill spent the latter years of his life at work as an artist in New York City, painting at his studio in Long Island City in Queens. All of the material on this page is copyright by estate of William Adie. Please respect him by not copying or distributing his material without permission.

Bill achieved a singular vision during his lifetime. His paintings, inspired by a wide range of influences over the course of his lifetime, speak to the conditions of both outer and inner life. Drawing on references that range from aboriginal art to Matisse and van Gogh, and using a vibrant palette to evoke a strong emotive presence, Bill draws us into active, otherworldly landscapes populated with human figures. Life is always in motion here; relationship and challenge are ever-present, as is a sense of both celebration and mystery.

Bill's final work was the decoration of his studio in Queens with the collected efforts of seven years of painting. Styled in the manner of great room collections of European royalty, Bill left a legacy of absolute modernism, interpreted through a lens of unwavering tradition. Those of us who visited his studio after his death were overwhelmed by the extraordinary impression the room left on everyone who walked in. It's safe to say nothing quite like it has been achieved elsewhere. His work plumbs the depths of the collective unconscious in a way Jung himself might have envied; yet it remains simple, accessible, and—above all—joyfully positive, in a way that inevitably reminds us of Matisse.

These paintings may look simple; yet they're anything but. As we shall see, Bill—a profound and even brilliant thinker (he was at the top of his graduating class at Rennsalear Polytechnic Institute in 1953) marshalled a complex and diverse set of visual references in his artwork, including many elements that may not be immediately recognizable except to the eye of a professional artist trained in art history. Add that to an indomitable spirit that faced down a debilitating alzheimer's-related disease and kept going, and you end up with a body of work that examines what it means to be human, to have courage and spirit, in a new and entirely unique way.

For more than fifty years of my own life, Bill was an invaluable personal friend, mentor, and fellow artist. He was by turns a businessman, pacifist, advisor, gourmet chef, painter, decorator, and art collector; but above all, and always, he believed in the mission of art to enliven men's souls and bring them together in harmony.

We used to discuss these things for hours at his apartment in New York; he was never at a loss for words on such matters, and fundamentally unerring in his guidance of the human spirit towards right thought and right action. Although Bill was never religious in the traditional sense of the word, he was always, quintessentially, spiritual; and that light shines through all of his art.

Bill's apartment at 178 east 80th street was an environment as unique as his studio. Check this link for photographs. Interested parties should contact doremishock@gmail.com if they have inquiries regarding a purchase of Bill's artwork.

Bill Adie

The artist on Individualism, Relationships and Performance

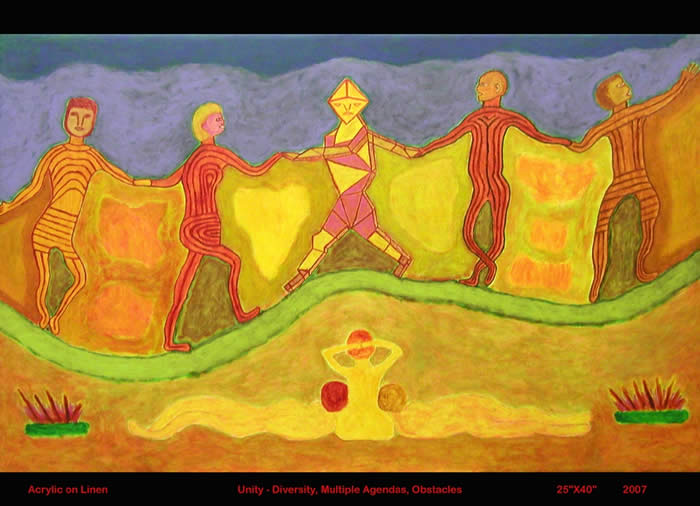

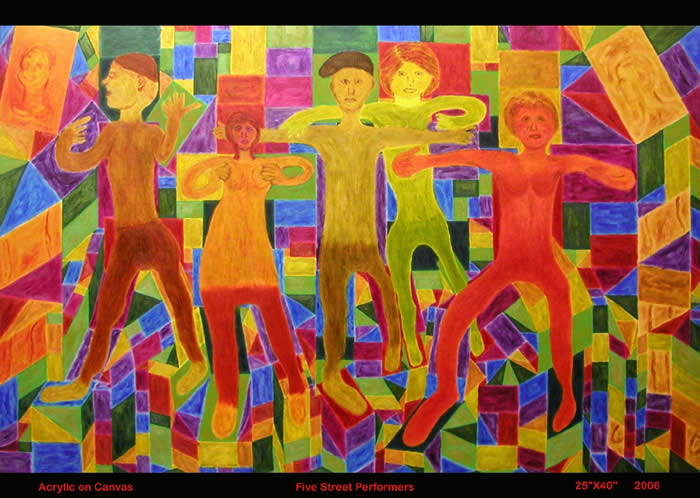

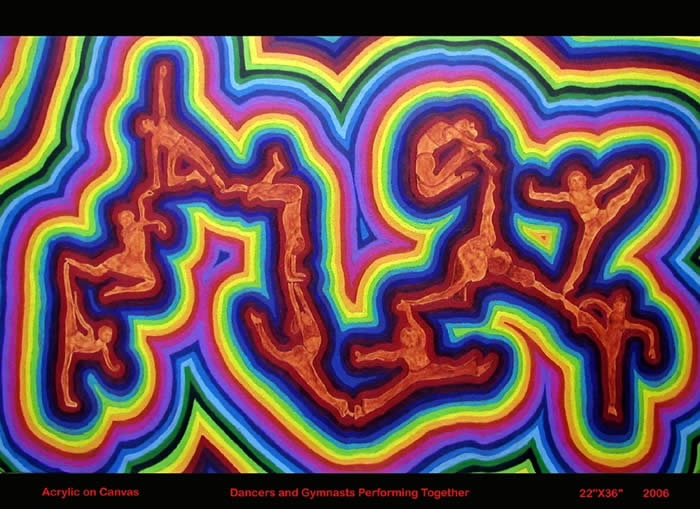

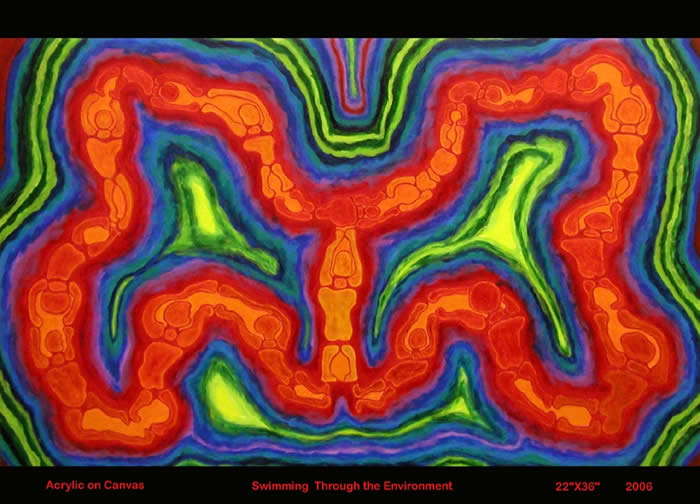

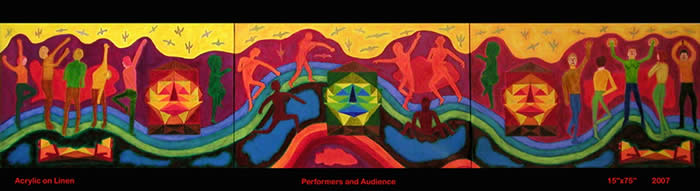

Bill's personal statement as provided to me in 2007. One is successful by performing by themselves and/or with groups and the community.

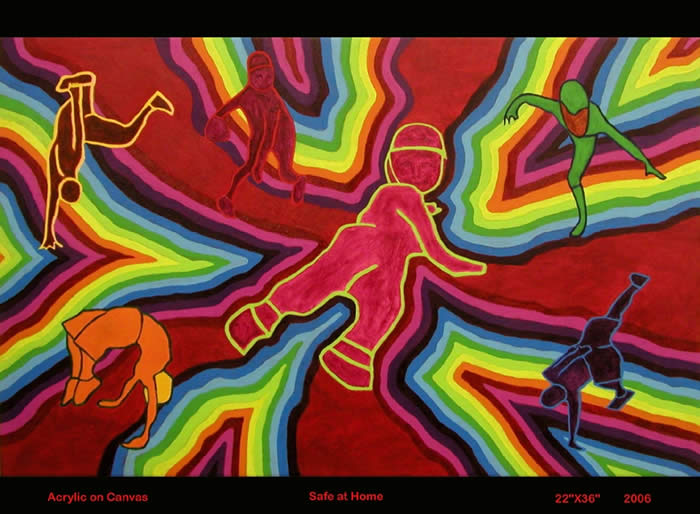

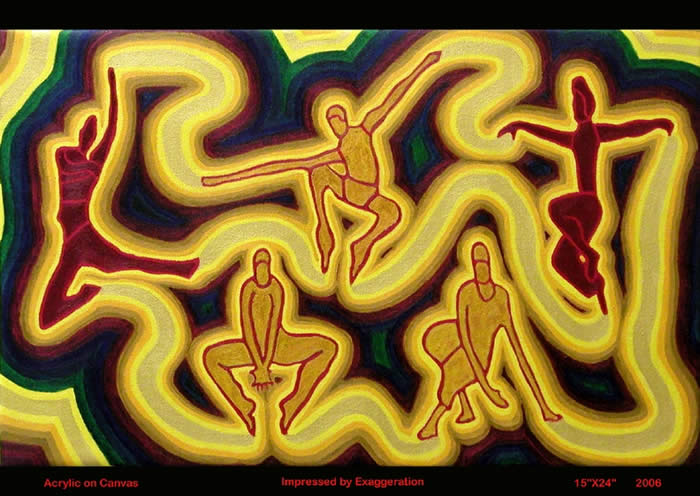

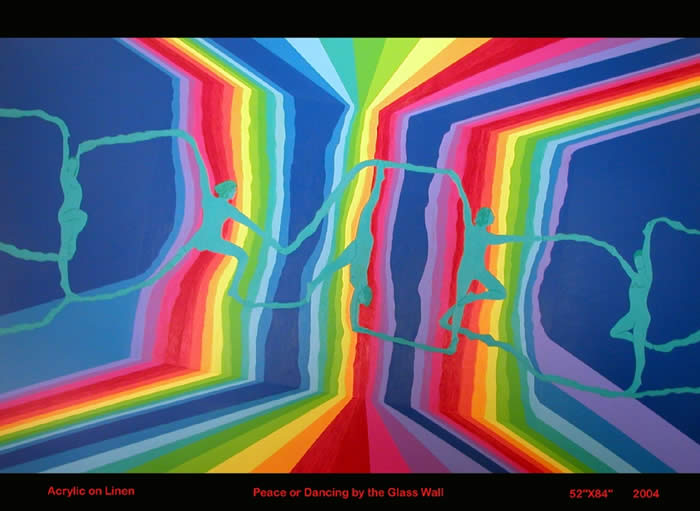

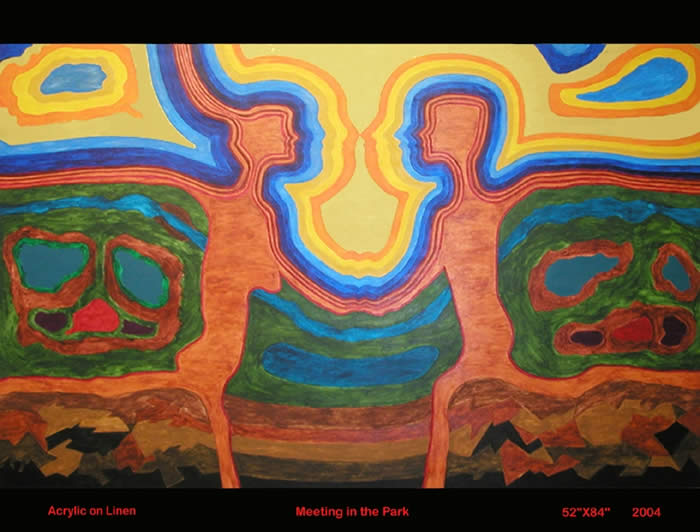

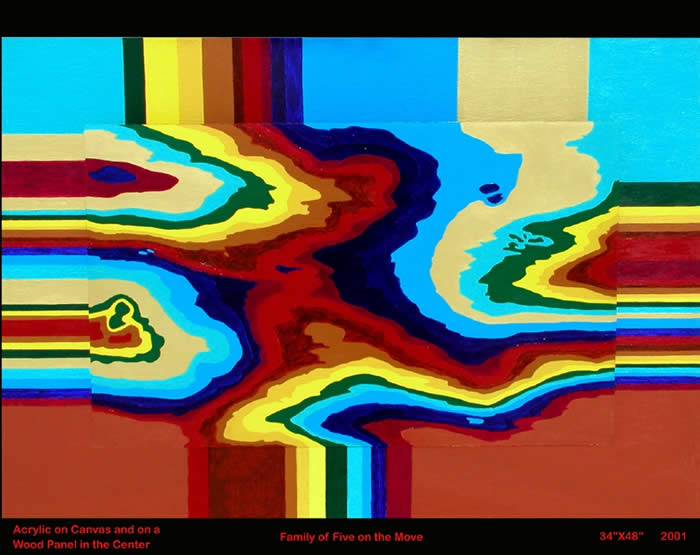

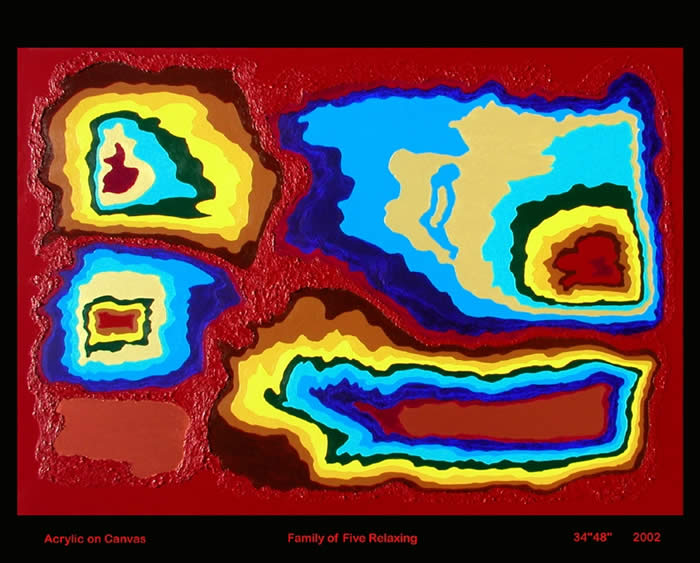

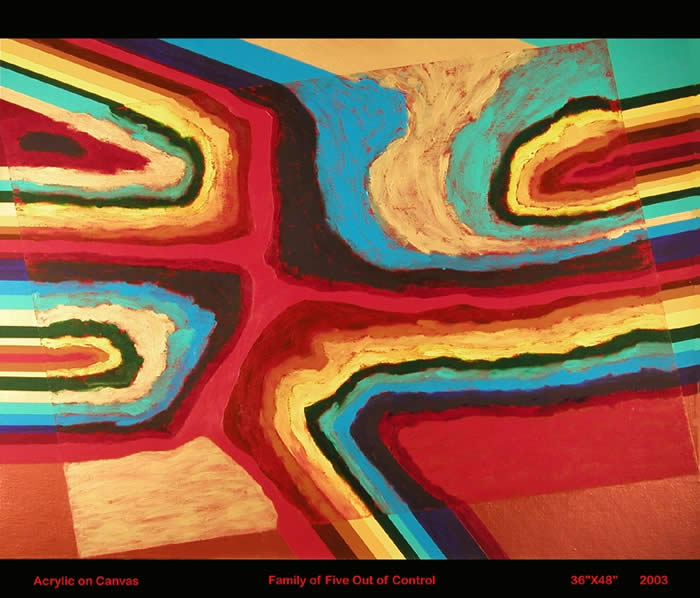

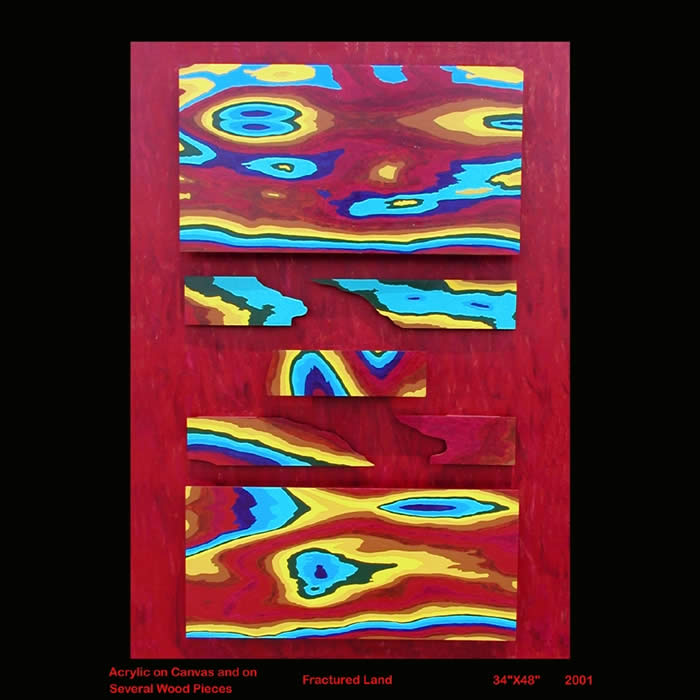

The paintings express situations using abstract themes and, in most cases, using abstract figures.

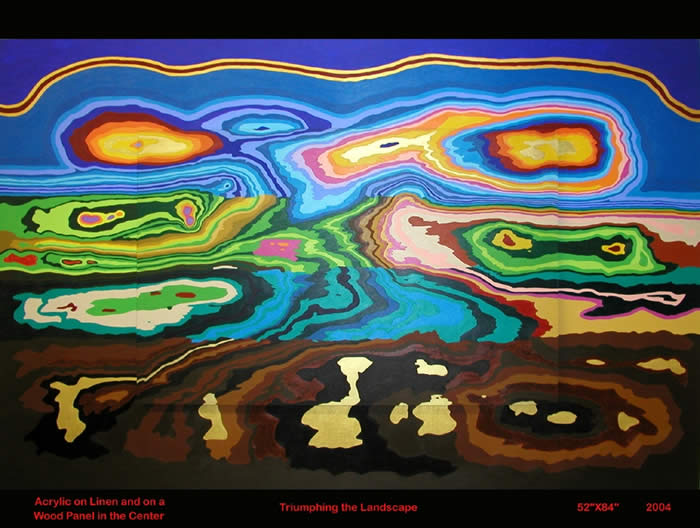

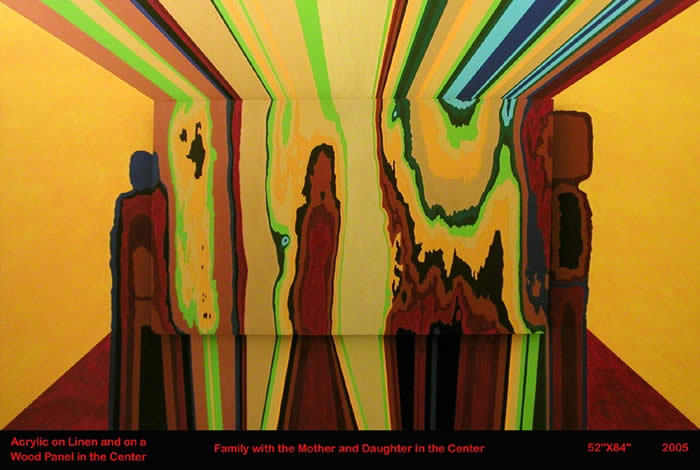

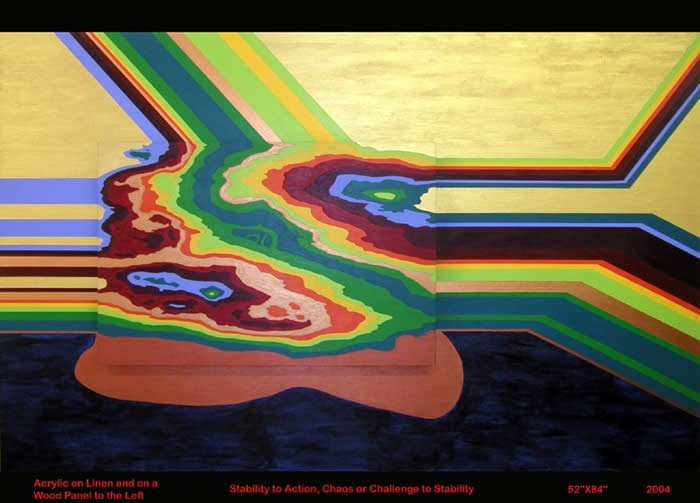

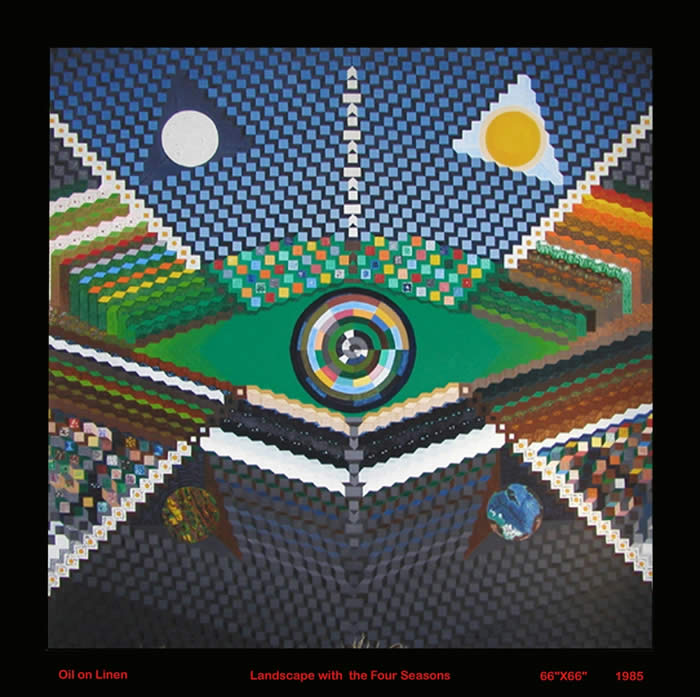

I use some of the following concepts to express the situations: - growth by referencing wood grains; - challenges by referencing waves and paths using chromatic spectra; - stability to action, chaos or challenge to stability using straight to irregular to straight waves; - opportunity by having alternative paths to successfully to go forward; - movement by having the figures active and irregular waves; cycles using some of the above.

- Using the abstract process leaves the viewer to participate by creating and relating to their own tales, fantasies or referencing a part of life. - My paintings are often sized using the Fibonacci and PHI (Golden Ratio)= 1.618. Positions and sizing in the painting also using the ratio.

A view of the Studio, Oct. 6, 2103. This was the final day Bill's last works could be seen in their entirety as he intended. Take note of the tight group of many small canvases on the left hand wall, which are actually intended to be viewed as a single piece (see below.) The distinction is important, because all the other small canvases in the room are clearly separated from one another.

Bill's apartment was decorated in much the same way with his art collection. His arrangements were a lifelong exercise in intention and deliberation; nothing was ever hung casually. Bills' approach to the display of paintings was drawn from his experiences in the traditional painting rooms of old european nobility,and took a great deal of time to think out. The collected works have to be understood not only as individual works, but as an installation.

Several of the paintings have three-dimensional mountings; the walkers in the upper middle right are one such painting. The yellow figure of the woman is mounted an inch or so above the surface of the supporting canvas.

The paintings are polished works of exquisite craftsmanship.

Neal Harris contemplating the installation of multiple small canvases on the back wall of the room. In the foreground is Bill's palette as he left it on the lat day he painted. Color experiments are evident.

A few of the larger works.

This exquisite composition owes more than a bit to van Gogh's "Starry Night," but remains entirely original. More on this piece below.

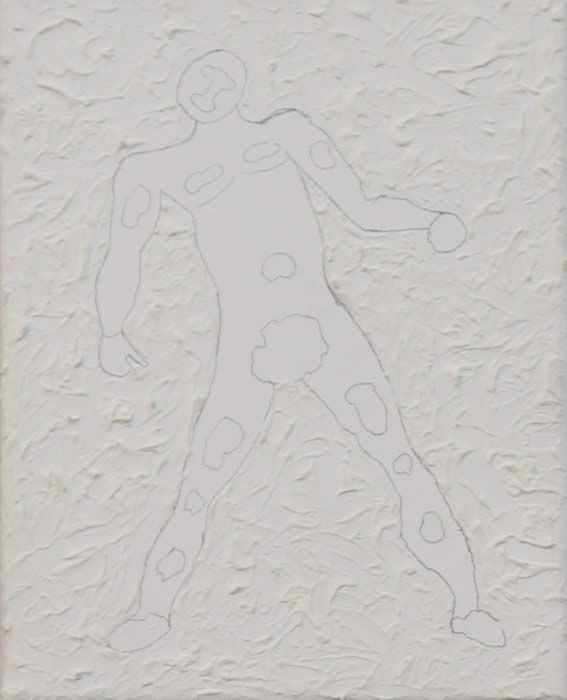

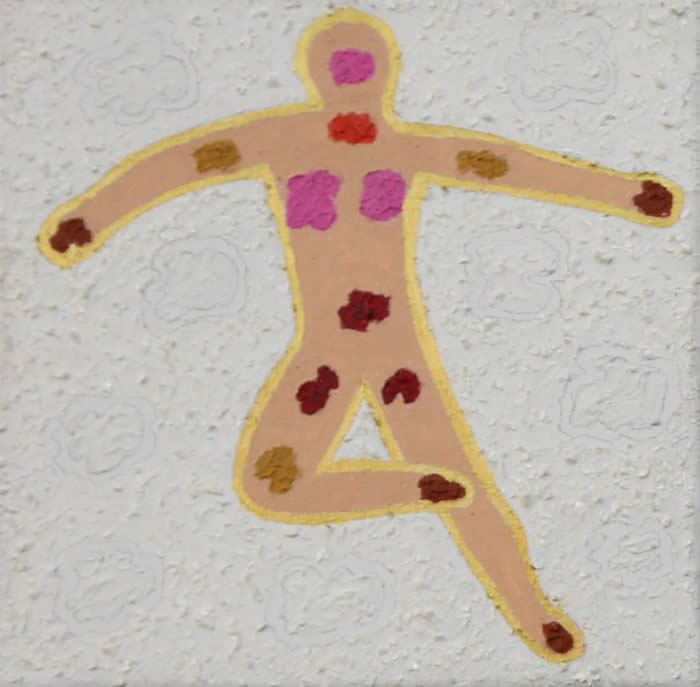

This evocative piece, the first in a group of smaller pieces which successfully reference both Australian aboriginal painting and Native American Mimbres iconography while, once again, remaining entirely original. The numinous reclining figure speaks to the inner depth and mystery Bill touched on again and again as his illness, PNFA (a rare disorder affecting the patient's ability to speak, but leaving his or her mental faculties entirely intact) progressed. Bill was entirely mute in his final years and able to communicate only sparingly through writing. His inner life, however, not only remained rich, but became richer with each year. His paintings attest to this deepening of the spirit, which he accepted and engaged with, allowing himself no bitterness whatsoever. Instead, he leaves us with an extraordinary affirmation of life and all its processes.

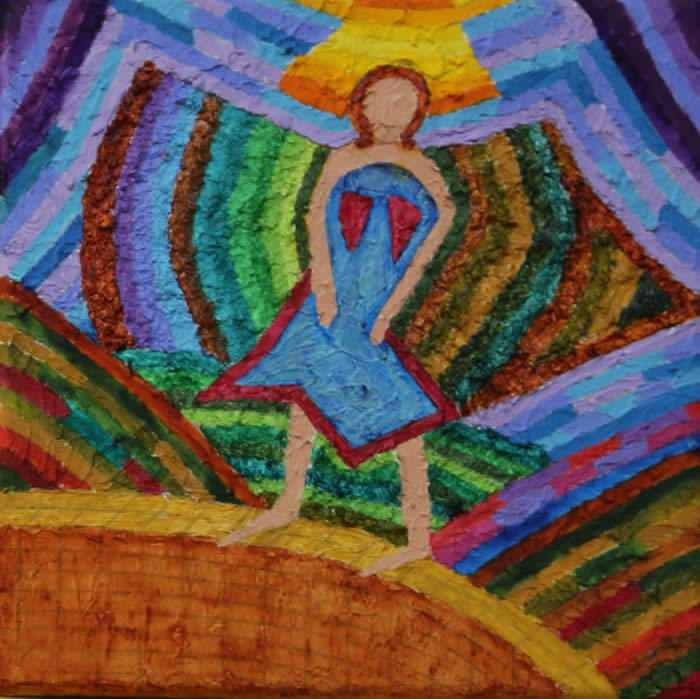

In the above painting we encounter the basic themes of geometery, landscape, and humanity, the three greatest leitmotifs of Bill's artistic vision. In this piece they have been distilled down to the essential, but still convey a vivifying timelessness expressed through the green cocoon or womb enveloping the figure. Paths move through the landscape; one leads through the sky like an umbilical cord to the sun.

Equally evocative is the near-yogic checkerboard plexus in the abdomen of the figure.

The second painting in the series. Reminding us of science-fiction art of the fifties, with—like many of his works, a touch of psychedelia (although I can personally attest that Bill definitely never used psychoactive drugs)— the figure seems trapped, and struggling. The essential qualities of life are nonetheless untouched; we're offered a sense of vitality despite the outer obstacles which crystallize the landscape. This small piece (about 9" x 12" is a testimony to the human spirit. It captures some of the struggles Bill went through as he progressively lost the ability to communicate with others verbally.

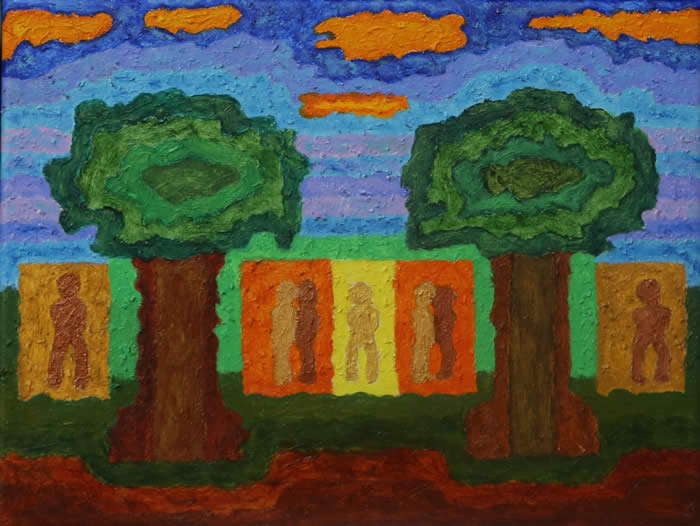

Third painting in this series. An oceanic, womblike environment holds elemental man and woman together in procreative symbiosis; solar influences suffuse the scene.

Fourth painting in the series. Simple yet masterful painterly devices cause Seurat and van Gogh to meet here in the textures and movement of landscape and sky; and perhaps we even catch a faint whiff of Breughel's peasants harvesting wheat here, although in an incredibly subtle device, the harvest is taking place within the man, not outside him.

The exuberance of the figure is, as with all of Bill's work, utterly unmistakable.

One of the most extraordinary paintings in the collection, now the property of one of Bill's grand-nieces (lucky girl!) This embryonic, elemental figure coiled into a figure-eight gesture of infinity leaves us with an impression of all of the mystery of life—and its extraordinary fecundity. The chakra-like wheels surrounding the figure impart their energies to it; a living being under construction by otherworldly forces. The primal qualities of a painting like this can't be denied.

This amazing piece echoes art across an eclectic range of twentieth-century influences, from De Chirico and surrealism through Keith Haring's cartoon works. In a sheer display of virtuosity it manages to reference architecture of both ancient and modern times. A glass-walled leaning tower of Pisa (shades of the world trade center) invites inspection, and renders multiple reflections of the viewer in the midst of a public forum, deftly alluded to by the steps in the upper right section of the painting.

Built on simple, iconic foundations (the diamonds, circles and ovals at the base of the piece) crystalline lines of mathematical influence penetrate the now (figures in the lower and middle ground) but give way to a more fluid and interactive set of curved lines in the future, as a single figure walks aways from us into the unknown.

The green figure on the left hand side of the piece, camouflaged and merging with the background, seems to represent a life-giving spiritual geometer, a hidden muse informing the process of architecture. Figures of this kind, common in allegorical paintings of the 19th century French Academy, find a new, more interesting, and profoundly unexpected place here.

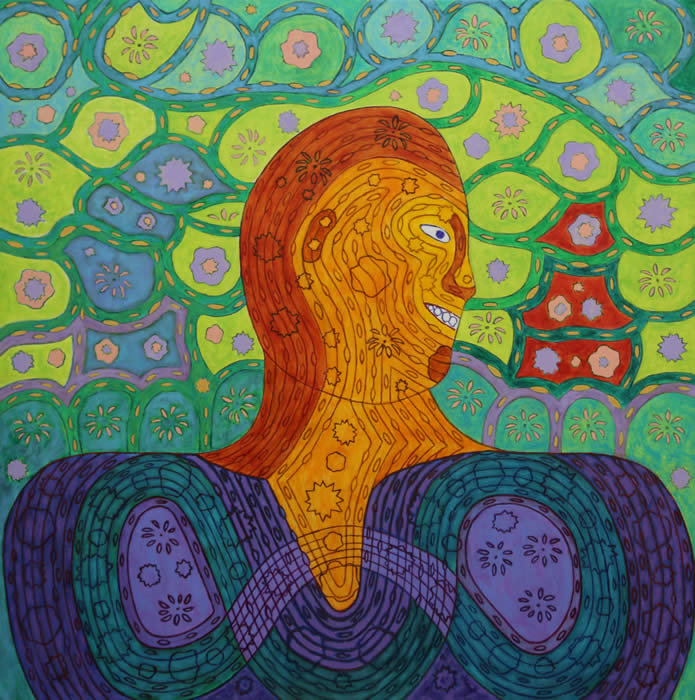

This painting is one of my personal favorites, despite its toothy and mildly disturbing grin.

I sold Bill a piece of mine with overtly biological themes in the late 1970's which was still hanging on his wall at the time of his death. I like to think that may have inspired this work, but at the same time this piece is so vastly superior I feel sure it's just a conceit of mine.

A wall of cells cleverly mimics the colorful patterns of fabrics and wallpapers common to late 19th and early 20th century painters like Matisse, Gaugin, van Gogh. The painting itself is an updated version of the portraiture common to that movement; but it manages to step out into the unknown and untested territory of everyman, abandoning individuality in a search for more universal properties. The palette speaks of vibrancy and life; green and blue cells and tissues reference the microbiological underpinnings of life which join all humans together. The figure, apparently a woman (read the long red hair) bespeaks fecundity and union through the undulating, joined lines of force created by her arms. Life, here,is a process not only of union and unity, but of fluidity and movement; and the figure-eight motion appears again here, morphing into a multiple of itself. The arms both create and embrace our subject's breasts; and all of her is suffused with the fundamental cellular identity of humanity itself. Playful floral elements mark the nuclei of some cells; this repeated motif brings a decidedly festive element into what might have otherwise appeared dry and medical.

In a nod to the consistent and sometimes difficult-to-discern landscape features found in almost every painting, the artist has given us a blue mountain (left) and red pagoda (right) on the horizon of the cellular landscape. As we recognize this, perhaps we once again begin to see an incredibly inventive update of van Gogh's treatments of skies.

The treatment of the face here is unqiue in all of Bill's art; I don't know what he was getting at, since he painted it after he lost the ability to communicate. It's possible this overt reference to teeth is a symbol of his wish to recover those lost abilities.

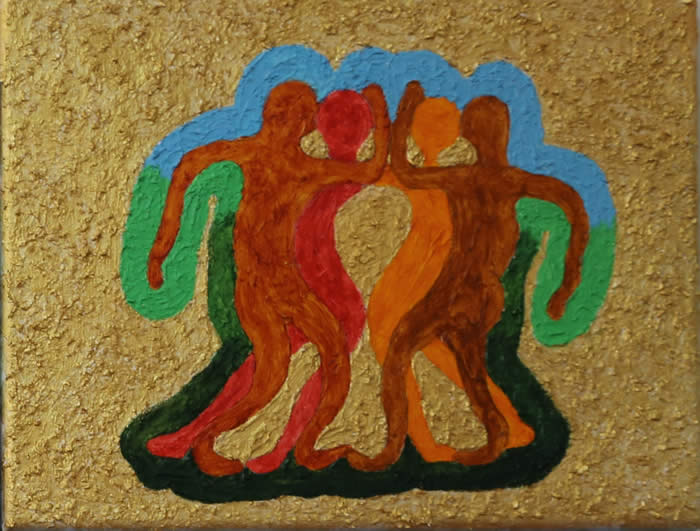

This piece, "Sculpture Garden," completed in 2007, marries Bill's lifelong fascination with geometric interpretations of landscape to an organic human element, exuberantly fleshy and unabashedly sexual.

The undulating landscape and sky are unmistakable referent to van Gogh's Starry Night; and indeed, his van Gogh book was at the top of his pile of books in the studio when he died, implying (as his paintings do) that he referred to it often. No copiest, Bill reinvented the dynamism of van Gogh's landscapes in his own inimitable style using the unlikely—yet undeniably successful— device of a blizzard of colorful triangles to pull off this visual stunt. The wheat fields are there; there are sunflowers, a sun; the curl of a snail-shell mountain on the horizon, and even a defiantly red and supremely assertive pegasus. This masterful combination of triangular geometry with organic curvature shouldn't work; but it does, and it not only works, it convinces.

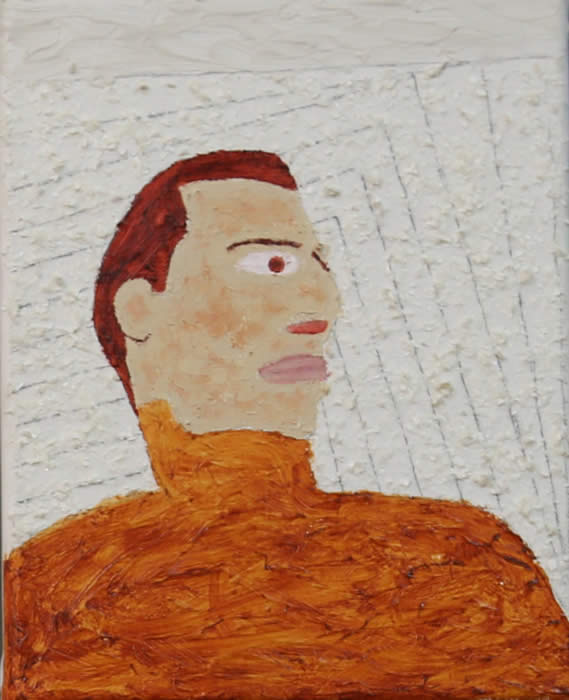

Another one of my favorites. This Buddha—the references are truly unavoidable—presides over both the studio and Bill's body of work with an ineffable and stoic calm that belies the inner turmoil Bill had to cope with as his speech faded away. Radiating the serene calm of a spirit that assures us no outer event can perturb or dissuade the artist—or the human being— from their appointed task in life, the lines of force meeting at the throat of the figure suggest hidden hands, folded in prayer.

This complex piece is composed of 22 separate small canvases. Bill had the habit for many years of arranging complex displays of works by multiple artists on the walls of his apartment. This piece is the culmination of that practice, and is—in its essence— a miniature version of the studio walls itself, in that the 22 pieces are not truly sepearte works, but one large work constructed of interrelated canvases.

Bill arranged these intentionally, and the lack of space between them verifies that he intended the work to be read this way.

These painting display a consistent and more painterly technique, with less of the polish found on other canvases. The apparent crudity is deceiving; each work is a carefully constructed composition. It's likely Bill painted these towards the end of his illness, as his ability to master fine detail deteriorated.

Let's review them one by one:

Center confused by the left and right. Acrylic on linen with wood panel mounted on canvas, 52 x 64, 2004.

|